The big man is all but glowing, basking in the spotlight of being asked to reflect on his legendary playing career and to offer some opinions on the state of the modern game.

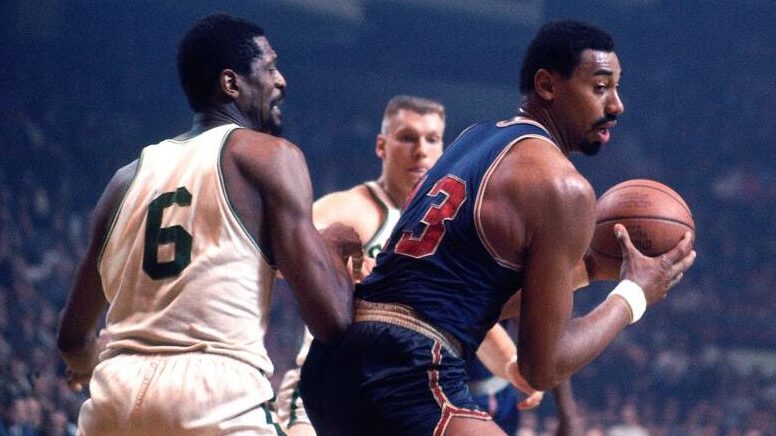

It’s February 1997 and the legendary Wilt Chamberlain, then 60 years old, was one of the stars of stars as the NBA was honoring its 50 greatest players during All-Star Weekend in Cleveland.

During our conversation, I asked Wilt, “Since we’re in Cleveland, would you mind if I asked you a few questions about the time you almost became a Cavalier?”

The 7-foot-1 Chamberlain paused, then let out a huge laugh and said, “You remember that, huh?”

Wilt didn’t want to talk specifics, but confirmed the team did indeed want him to come out of retirement and play for it in November 1979.

“The Cavs did want me (to return to the NBA), but they weren’t the only ones,” he said. “They weren’t the first team, nor the last, to talk to me (about playing again).”

“Bulls, Cavaliers, Nets, Knicks twice, Sixers twice, Mavericks, Suns, Clippers — those are all the teams who tried to get me in the last decade,” Chamberlain said before accepting the Living Legend Award from the Philadelphia Sports Writers Association at its annual dinner in 1991.

In transition

Nick Mileti had owned the Cavaliers since they joined the NBA for the 1971 season. After reaching the playoffs for three consecutive seasons (1976 through 1978), Cleveland fell on hard times in 1979, dipping to 30-52, which led to Bill Fitch, the team’s first head coach and general manager, resigning on May 23, 1979.

Two months later, Mileti hired Stan Albeck as the team’s second head coach.

Therein lies the tie to Chamberlain.

Bouncing elsewhere

Wilt retired from the NBA after the 1972-73 season with the Los Angeles Lakers, doing so as the league’s all-time leader in points and rebounds in a game, season and career, holding almost 80 individual records compiled during 14 seasons.

His next move was to bolt to the ABA’s San Diego Conquistadors as player-coach for the 1973-74 season. However, a court ruled Wilt could not play as the Lakers still held an option on his contract, so player-coach became coach.

Chamberlain’s contract reportedly called for a salary of $600,000 a year, nearly double what he had made in his final season with the Lakers.

His assistant in San Diego was none other than Albeck.

An amazing amount of stories about Chamberlain’s one season with the ABA are told in Terry Pluto’s outstanding book, “Loose Balls,” and through them it’s clear while Wilt had the title, the responsibilities and duties fell upon the shoulders of Albeck, to which even Chamberlain admitted.

“First of all, I never visualized myself as a coach,” he told Bob Wolf of the Los Angeles Times in July 1990. “I had help from Albeck, and he was more the coach and me a figurehead. But actually, I think we had a joint operation.”

The Conquistadors finished the regular season 37-47, knocked off the Denver Nuggets in a one-game showdown for the final playoff spot, then were eliminated from the postseason by the Utah Stars in six games.

“I felt from the start that Stan (Albeck) was the real coach,” he said. “He never placated me, but he was willing to do whatever I wanted him to do. A lot of the press would ask him, ‘Does Wilt show up for practice?’ He handled it extremely well.”

Stan’s grand plan

It was Albeck who first broached the idea of attempting to lure Wilt back to the league. The Chicago Bulls and Phoenix Suns had attempted to do so previously, but came up short.

“It was about 2 1/2 months ago,” then-Cavaliers general manager Ron Hrovat said in November 1979. “Jim (player personnel director Jimmy Rodgers), Stan and I were sitting around, and Stan says, ‘I’ll give you a wild one. Let’s go out and get Wilt.’

“Well, I looked at him and said, ‘Are you nuts?’ Stan said rumor was that Wilt was in better shape than ever, so we contacted him.

“In casual conversation, he said he was only interested in playing for a year and that killed it. But the subject came up again, and Nick and his wife, Gretchen, had lunch with him last Thursday. Wilt agreed then to meet with Stan and me. So we had a long lunch with him, then we made him a firm offer on Tuesday.”

Matters of fact

In his 1991 book, “A View from Above,” Chamberlain talked extensively about teams wanting him to return to the court.

“Since my retirement, some things have happened that make me think I was regarded in a much higher light than even I thought I was.

“In the past 15 years, no fewer than half a dozen NBA teams have tried to get me to come out of retirement and play.”

Chamberlain admitted he was tempted to give it a shot.

“I was intrigued from time to time by these offers, not because of the money but because it would have been the first time a person who was already in the (basketball) Hall of Fame came out of retirement to play again,” he said.

“Obviously, all of the people in the Hall are retired, in fact, most of them are dead, so it was a unique situation.”

Reaching for the stars

Mileti had one goal for the Cavaliers and believed the legendary Chamberlain could help them obtain it.

“I have one goal, and that’s to get a championship trophy,” Mileti said at the time. “Wilt can help us do that.

“His presence will be felt on and off the court.”

Word gets out

News of the Cavaliers wooing Chamberlain was broken by the Plain Dealer, which Hrovat said bothered the Basketball Hall of Famer. The team and Wilt were attempting to keep their negotiations behind closed doors.

“He’s very sensitive about this sort of thing. He really is,” Hrovat said. “It all hinges on his pride. Nothing else is in the way. He’s only thinking about whether he can contribute.”

Wilt takes stock of Cavs

Chamberlain assessed the Cavaliers’ roster, which included fledgling star Mike Mitchell, popular veterans such as Austin Carr, Campy Russell, Foots Walker, Bingo Smith and John Lambert (all holdovers from the 1976 Miracle of Richfield squad), solid contributors Randy Smith, Kenny Carr, Dave Robisch, youngster Bill Willoughby and an end-of-the-line Walt Frazier.

“He did some checking on this team, and he was convinced the Cavaliers could do it,” Hrovat said. “He also knows Stan, and he felt he could play for him.”

Hrovat said the talks included details about his role.

“I also asked Wilt whether he was willing to go through the traveling again. He said, ‘I wouldn’t be talking to you now if I wasn’t,'” Hrovat said. “He also said he was in shape to rebound and to play defense.

“But he admitted it would take him anywhere from a week to two months to make himself into a productive offensive player. That takes a little different touch.”

Hall of Fame coach Larry Brown said Chamberlain talked to him about playing with the Cavaliers.

“He came to me and said Cleveland wanted to sign him and he asked me if I thought he could still play,” Brown said. “I said, ‘Yeah, but I don’t know how happy you’d be playing on a limited basis.’ ”

Albeck was more singular with Chamberlain about a potential role with the Cavaliers, but Wilt had other ideas.

“I told him I just wanted him to rebound,” Albeck told the great Peter Vecsey, then writing for the New York Post, in June 2005. “He said, ‘The hell with that, I want to shoot threes.’ I told him, ‘Fine, shoot all the threes you want.’ ”

Money matters

Hrovat denied a published report that said Chamberlain’s base salary would be $150,000.

“No, that base is wrong,” he said. “Much of the salary is based on incentives. If he reaches most or all of those, he will be one of the higher-paid guys in the league.”

Hrovat said Mileti and the franchise were not attempting to lure Wilt out of retirement on the cheap.

“The terms of the contract are very generous,” he said. “The more time he plays, the more the bonuses come into play. That’s the key in the bonus arrangement time played.

“Wilt definitely doesn’t need the money. That’s why I think this is so beautiful. He wouldn’t be coming back out of need — he would be coming back with the idea of something else to conquer.”

The Cavaliers wanted Chamberlain to agree to play two seasons.

“We did not want him for one year,” Hrovat said. “We are really trying to build for the future. Go with Wilt for two years to give us time for further developments.”

Asked about the prospects of adding the 43-year-old Chamberlain to his team’s roster, Albeck was both uncertain, then certain.

“I have no idea of what’s going to happen,” he told Sheldon Ocker of the Akron Beacon Journal. “But can he play?

“Very definitely.”

Clearing a path

While his contractual obligations with the Lakers prevented Chamberlain from playing for the Conquistadors in the ABA in 1974, they were no longer a roadblock to him returning to the NBA with the Cavaliers in 1979.

Lakers owner Dr. Jerry Buss said his team would not ask Cleveland for compensation for signing Chamberlain, should it take place.

“I think it would be great for the NBA if Wilt were to play and I do not want to put anything in the way of this happening,” Buss told the Associated Press on Nov. 20, 1979. “I would enjoy seeing him play again, so I am sure would thousands of basketball fans.”

Getting down to it

Hrovat said the team had a lengthy meeting with Chamberlain, which took place Nov. 12, 1979, according to United Press International, four days after meeting with Mileti and his wife.

“I was in Los Angeles (on) Monday and we met with Wilt for three hours,” he told the Associated Press on Nov. 16, 1979. “I talked to him on the phone again Wednesday.”

The first-year GM, a Cleveland native who died Dec. 9, 2013 at age 79 in Las Vegas, said he knew better than to press Chamberlain for an answer.

“I didn’t give Wilt any deadline to give us an answer, but I anticipate he will give us one very soon.”

Some perspective

Before we get to how this story concludes, while many stories of the 1997 All-Star Weekend focus on Wilt’s famous conversation with Michael Jordan about who the greatest player in the history of the game was, a young Kobe Bryant winning the Slam Dunk Contest — at age 18, its youngest-ever champion — in his All-Star Weekend debut, and, of course, the NBA honoring its 50 greatest players in its history, I spotted something else.

Wilt was pushing a young girl in a wheelchair throughout the weekend’s festivities, helping her to obtain autographs from the game’s greats and serving as her personal tour guide.

Thanks to Philadelphia Daily News copy editor Mark Perner, it was discovered the young lady was 16-year-old Stephanie, who had written Chamberlain four years previous asking for his autograph when she was 12. It took three years for her letter to reach Wilt and upon receiving it, he discovered Stephanie was the granddaughter of former Philadelphia Warriors teammate, Paul Arizin, himself a Hall of Famer and 10-time All-Star.

Wilt then called Stephanie, apologizing for taking so long to respond, and they formed a friendship and Chamberlain called her father, Paul’s son, Mike, to thank him for Stephanie sending him the letter.

As Perner pointed out, there was something Stephanie had not disclosed — she was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor.

Wilt was understandably shaken. He vowed to stay in touch with Stephanie and her family and he proved to be a man of his word.

All of which led to him be spotted escorting Stephanie around All-Star Weekend four years later.

“We lost Steph on July 30, 1997,” her father wrote in a first-person story for the Philadelphia Daily News in 1999. “From the time they first spoke, Wilt called Steph every Friday night for the rest of her life.”

Against the wind

While the Cavaliers waited to hear from Chamberlain in 1979, they kept their hopes up.

“I am optimistic Chamberlain will sign,” Mileti said. “However, I’m still cautious. I have been here before. Nothing is certain until it’s certain.”

The Cavaliers took the initiative to hand-deliver a contract to him.

However, they blew it — literally.

The team’s Hall of Fame radio broadcaster, Joe Tait, said as much.

“When the Cavs tried to get Wilt a contract, he wasn’t home (in Bel Air, Calif),” Tait said in 1991. “So they stuck it in the fence by the gate of his estate.

“When Wilt got home, he found pages of the contract all over his front lawn. A big wind came and blew it all over the place.”

Vecsey corroborated Tait’s recollection of that turn of events.

“Cavs GM Ron Hrovat, a basketball neophyte, was entrusted with the responsibility of hand-delivering the contract to Chamberlain’s palatial home in Bel Air,” the Hall of Famer wrote. “Nobody was there when Hrovat arrived, so he stuck the contract in the gate. By the time Chamberlain showed up, the papers were strewn around his yard.”

Which did not sit well with Wilt.

“Chamberlain immediately got Albeck on the phone,” Vecsey wrote. “‘Forget it, Little Man,’ he said, using his endearing nickname for Albeck.

“I can’t play for a team that handles its business like that.”

Albeck lamented how the Cavaliers’ pursuit of Chamberlain concluded.

“He was this close to coming back,” he told Vecsey, holding his thumb and index finger an inch apart.

More in-depth

Chamberlain dove deeper about potential comebacks in his book.

“Coming back would have been a great, fun challenge for me,” he wrote. “I had a feeling I would help these teams, and I will always wonder, ‘What if…?’ ”

He was also matter of fact about the level at which he would have played if he had opted to play again.

“There is no doubt in my mind I would have led the league in rebounding,” Chamberlain said. “It’s not even a question. But it would have been at a cost, an emotional strain I no longer needed.”

He spoke about 76ers owner Harold Katz attempting to lure him out of retirement in 1982.

“I was positive I could do it,” he told Milton Richman of UPI in 1982. “My physical condition certainly was no barrier because has hardly been a day I haven’t competed in some form of sport or other, whether it was racquetball, paddle ball, swimming or running, since I retired from basketball in 1973.

“I weighed around 300 or 305 then and I’m down to around 270 now. I’m in much better physical shape than when I quit and if you remember, I wasn’t too bad then and even led the league in three or four categories.”

Chamberlain finally decided he just didn’t want to play pro basketball again, especially considering all he had accomplished, including winning a pair of NBA championships.

“In the end, I simply didn’t have a strong desire to play again,” he wrote in his book. “That’s the only thing that stopped me. I would have needed this strong desire because of my absolute need to represent myself properly and give the fans who buy tickets their money’s worth.”

“I felt it was better to remain something special in the fans’ eyes than to come back and be less than what was expected of me.

“And less than I expected of myself.”

About the Cavaliers…

The 1979-80 Cavaliers finished 37-45 and missed the playoffs. Albeck lasted only one season in Cleveland, but landed the next season with the San Antonio Spurs. Hrovat was soon fired by the team’s new owner, the infamous Ted Stepien.

And Wilt never played again, for the Cavaliers or any other team, for that matter.

“Come February, where do you think I’d rather be?” he told People Magazine in a 1984 interview. “In Cleveland, trying to plow my way through a snowstorm to get to a game or on the beach in Hawaii, board sailing and chasing girls?”

Thirteen years later at All-Star Weekend in Cleveland, I asked Wilt about that quote, to which he let out another huge laugh.

“That was a long time ago and I’m happy to be here now,” he said through a smile.

Did he seriously consider joining the Cavaliers?

“Of course!” he laughed.

Wilt then winked and shook my hand, which was akin to doing so with a catcher’s mitt.

“It’s always great to be wanted,” he said through a smile.

Wilt Chamberlain died at his home from heart disease Oct. 12, 1999.

He was 63.